Today the attention of international media is set on other humanitarian crises, leaving many others on the second page and some almost completely forgotten. It is the case of Afghanistan, which is facing a dramatic situation: almost the entire population that has not fled the country lives in a highly emergency context and where humanitarian aid struggles to arrive. The conditions of women, especially of those who have to take care of their families on their own, are the most alarming.

The position of women and children

For Afghani women, the return of the Taliban to power has entailed the reinstatement of strong restrictions and discriminations. Today, women can no longer leave their homes without being accompanied by a male member of their family. Due to the high rate of men who have died in recent conflicts or as a result of the pandemic and other widespread diseases, over 2 million women are widows. Their possibilities to find a job, or even of begging on the streets on their own, are hence almost absent. For them, not only autonomy and economic independence have become impractical, but also their survival conditions and their access to food is at risk.

To cope with such situations, many children are compelled to work or beg on the streets, with all the psychological, developmental and physical risks linked to such conditions. In this light, the right to education is becoming more and more precarious, affecting mostly girls, who have recently been totally excluded from secondary education: a fundamental tool also to tackle the traditional and spread use to force them into marriage for economic reasons.

At last, the most dramatic consequence is that of many mothers who, unable to keep ensuring at least one meal per day, see no other option than abandoning their children in front of orphanages. Children are therefore extremely vulnerable, with more than half of the population under five years old suffering from acute malnutrition.

To survive in Robat Sangi

In the mountains of the northwestern province of Herat, in the district of Robat Sangi, the severe three year-lasting drought has greatly reduced the traditional agricultural crops. As a result, deep-rooted rural customs, such as subsistence economy and solidarity among neighbors, are no longer sustainable and hunger is spreading. In this context, many have left. Among them, some have managed to immigrate, while others have joined the displaced masses surviving in the streets of the country's major cities. The social fabric is thus gradually being torn apart under the weight of extreme daily difficulties. On top of this, the arrival of winter has brought with it a general worsening of living conditions, as temperatures in the region drop even below -10°C and many roads find themselves blocked, compromising access to essential goods and services.

The few remaining residents of the Robat Sangi area describe this past year as the worst they can remember. More than 70 km away from the nearest city, reachable by winding mountain roads often blocked by snowstorms or thick fog, the only sources of income are currently relegated to the few crops resistant to adverse conditions, such as licorice. This plant is largely present in the region and the harvest of its roots takes place between autumn and winter. In the villages of Qanat Wakil and Dezwari, the remaining families go to the fields: adults with pickaxes and small children behind tractors that move the soil and bring the roots to the surface. In the villages, retailers buy 4 kg of roots for the equivalent of nearly 1 USD.

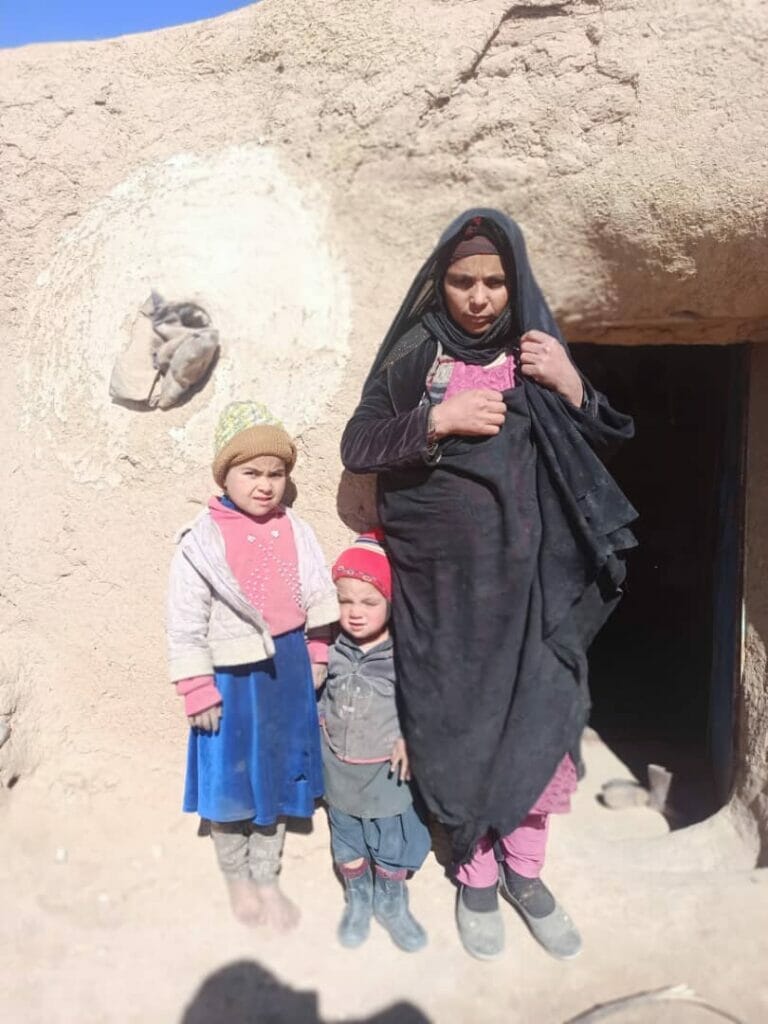

Morwarid’s family

The gathering of licorice roots sustains the family of Morwarid. A mother of six, she found herself in charge of her family about a year and a half ago after her husband, who was addicted to opiates, abandoned them. This condition is very common in rural Afghanistan, where people working in opium fields end up consuming the plant to avoid fatigue and hunger while harvesting.

Within 2 or 3 days, the mother and her children manage to gather the equivalent of nearly 1 USD worth of roots. With what they earn, they buy sugar, tea and rice, products that they find in the sale points that they have to reach by paying the fare of shared cars. If they don't have enough money, they go there by donkey or on foot. Most of the time, however, Morwarid's family subsists only on dry bread and tea, sitting in the one room of their earthen house. For entire days, they walk around looking for some flour or anything else to eat. Until a few years back, families from the area who lived off the sale and consumption of wheat used to offer a third of their harvest to their neighbors in need. Today, those same families find themselves struggling every day to secure food and heat in their own homes.

The eldest daughter, how is now 16, left the house three years ago when she was given away in marriage due to a pending debt. The other children are 12, 8, 4 and 2 years old. A sixth child, Ahmad, died last January from the cold: he was just 6 years old. However, the cold is not an end in itself diagnosis. It is a structural phenomenon linked to poverty and the resulting inaccessibility to basic services. As a matter of fact, in an area such as Robat Sangi, dying of cold in one's own home is the consequence of the economic and concrete difficulty in finding materials to keep warm and in accessing health services, reinforced by the fact that the mother was the sole provider for Ahmad. Where she lives, and as a single woman, she has no alternatives.

Morwarid and her youngest children, one week after Ahmad's death

The health system

After years of conflict, epidemics related to hygiene and food shortages, and the current health crisis related to Covid-19, the national health system is very limited in resources and facilities. These deficiencies have led to an increasing prevalence of corrupt practices, where medical services are often conditioned on obtaining a personal benefit. In such a system, it costs over 10 USD to fill a prescription, plus the cost of getting to the nearest health center. In total, for Morwarid's family, a doctor's visit represents, at best, a month worth of work in the fields. When Ahmad started to fall ill, his mother asked neighbors for any amount of money in order to get him to a doctor, the nearest being at about 20 km away. However, no one had enough.

The renewal of humanitarian aid

Despite the difficult penetrability of cash in the country due to the severe crisis of the banking system, the negotiations with the authorities and the reluctance of some donors due to the political situation, it has been gradually possible to reintroduce humanitarian aid programs of monetary nature. Thanks to the rooted presence and the possibility of action of our local partner Rural Rehabilitation Association for Afghanistan (RRAA), we have been able to implement a Cash for Food project in the rural areas of Robat Sangi, precisely in support of the women who found themselves at the head of their families. Morwarid’s family has thus become one of the 180 ones currently benefiting from our program, counting overall more than 1000 people of whom ¾ are children.

Among the beneficiaries, 95,5% resulted to suffer from hunger and 71,1% from severe hunger during the assessment, some of them having eaten just bread for a couple of weeks. Their severe lack of income has forced them to adopt many negative mechanisms: the recurrent borrowing of money to buy food; the cutting off on expenses such as health and education; selling whatever item available such as furniture, appliances, doors and so far as their income generating equipment or means of transport; reducing the number of meals per day or readdress the quantities from adults to children. To tackle these negative coping techniques and in general the harsh conditions in which the selected households survive, the aid takes the form of the distribution of money and vouchers for the equivalent of 90 USD per month per family – amount based on the average number of members per family and on regional costs and availability - for the purchase of food and heating materials.

During the first distribution, some women shared with our partner's staff how they plan to bring positive changes to their living situations. With the end of winter, the priority of heating ceases. Moreover, food production, access, and availability should become easier. Therefore, in the next months the program could also serve to hopefully and gradually get part of the children back in school. For the time being, our implementing partner will carry on a post distribution monitoring to hear the beneficiaries’ impressions and gather existing success stories, along with possible complaints or misuses of the cash. Following this activity, a second round of distribution will be organized accordingly. Moreover, the intent is still to try and scale up on the project’s beneficiaries, but the banking crisis holds back on this objective.

The recent events of Morwarid's family display the tragedies currently plaguing Afghanistan. In fact, child labor and deaths, forced marriage for girls, opiate addiction and hunger are far from isolated phenomena.

"I lost my Jigar Goosha (part of my heart) because of poverty. Only God knows what happens in the heart of a mother who loses her child. It cannot be put into words. I don't wish this to any mother." These are the words of Morwarid. Her story, like that of so many other Afghani women whose names and existences we can hardly imagine, is made of grueling barriers and daily efforts. It is why external support, which is currently the only available one, is as fundamental as it is urgent. The continuity of emergency programs must be guaranteed by the international community, also at each governmental level, along with finding a solution to the local banking situation. Afghani population cannot afford cuts in humanitarian response funds at the moment: they need money to feed their children.